How China Misallocates Human Capital

There is a nifty phenomenon I have observed in the United States. The best and brightest often consider starting their own company as potential route in life, rather than conform to a specific preset track of academia or high-paying careers. The best and brightest often hold a mindset that, even if they fail, they can always rely on their own wits to succeed in life despite the odds being stacked against them.

This is not the case in China.

While the United States may sort its best and brightest using an SAT, the equivalent of such an exam is known as the Gaokao in China. This test is hard. I often hear my mother and aunt worrying over my cousin (who is currently a 14 year old just starting high school) and how he will fare on the exam. Every child in China studies like a maniac for this exam. For them, it is the difference between having a real chance at going to a good college (and therefore having a chance at a high-paying career) vs being relegated to go to a crappy trade school and become some poor plumber.

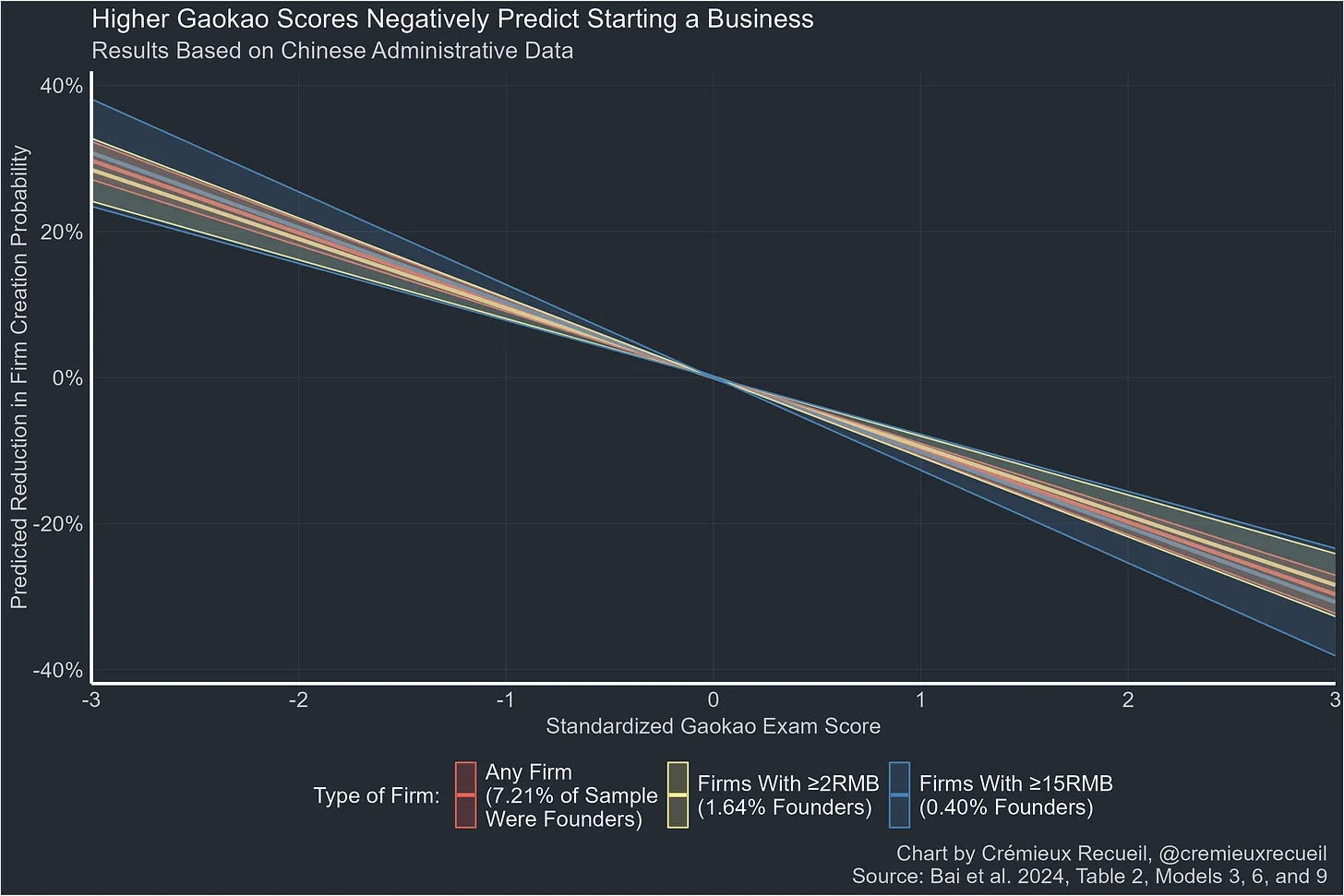

Almost tragically, however, higher Gaokao scores correlate negatively with starting a company (please see this wonderful chart made by Cremieux).

Cremieux argues it is because China is funnelling its best and brightest into working jobs in its government, but I think there is a different side to this.

My thesis is simple. The best and brightest kids in China have worked practically their entire lives to absolutely obliterate their peers in the Gaokao. The reason why they have tried so hard is because of a single principle their parents have drilled day and night into their minds: good grades means having a stable and prosperous career. So, after putting in so much work towards this one goal of having a good score, the vast majority of the top-scorers will choose to claim their prize (a cushy job) instead of taking a massive risk by starting a company.

If the American Dream is to become wealthy beyond one’s wildest imagination, the Chinese Dream is to become just better off than the generation before them.

This divergence in cultural aspirations reflects deeper societal structures and values. In the United States, the narrative of individualism and risk-taking permeates every aspect of life, especially in the context of career and innovation. The concept of failure, while not exactly celebrated, is often viewed as a stepping stone toward eventual success. Silicon Valley folklore is full of stories about entrepreneurs who endured multiple failures before hitting it big. This normalization of risk creates a fertile ground for ambitious individuals to try, fail, and try again.

In China, however, the stakes are different. The path to upward mobility is often linear and heavily reliant on academic performance. The Gaokao, often described as a life-determining exam, is not just a test; it is a societal filter. Families pour immense resources into preparing their children for this single measure of success, and the pressure to perform is enormous. This pressure creates an environment where conformity and discipline are prized over creativity and risk-taking.

But the impact of the Gaokao system extends beyond just career choices—it shapes mindsets. After years of intense preparation for a singular goal, the idea of deviating from a secure path feels almost like a betrayal of one's effort and family sacrifices. Starting a company is not just risky in a financial sense; it is culturally disruptive. For many, the social and familial consequences of failure are too great to bear.

Yet, there is another layer to this phenomenon. The structure of opportunity in China is also less forgiving for entrepreneurs compared to the United States. Access to capital, networks, and institutional support is often concentrated among those who already have connections or wealth. Even the Chinese government’s emphasis on innovation often aligns with national priorities, steering resources toward established sectors or state-backed enterprises rather than grassroots entrepreneurship.

The culture in China does not reward risk. Even perhaps the prime examples of what folks would call “Chinese innovation and risk-taking” are modelled after major American successes. Alibaba modelled itself after Amazon. Tiktok’s innovation in short-form video existed in Vine. Didi is a direct copy of Uber. The most successful Chinese firms are ones that take proven American ideas, and scale them up for the Chinese market. Even amongst the most prominent of Chinese tech giants, you can see a pattern of avoiding risk.

Ultimately, the contrast between the American Dream and the Chinese Dream is not just about individual ambition but also about collective aspirations. The American Dream thrives on the belief in the limitless potential of the individual and the value of standing out. The Chinese Dream, shaped by millennia of collective responsibility and hierarchical structures, prioritizes stability and incremental progress.